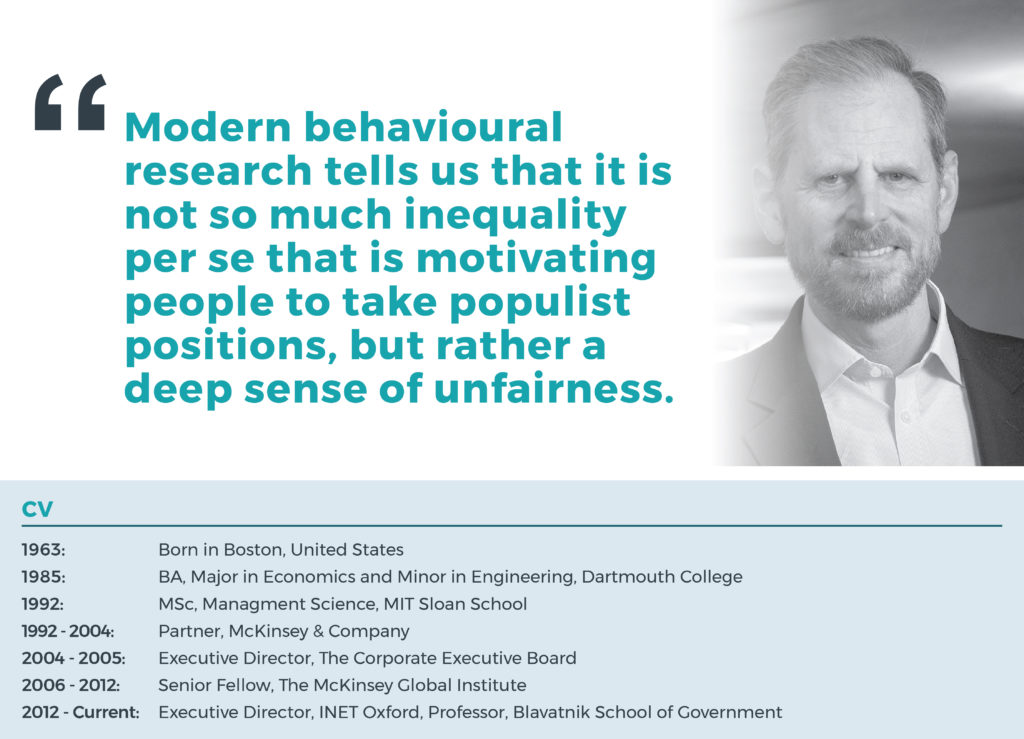

We had the pleasure of speaking with Professor Eric Beinhocker, Executive Director of the Institute for New Economic Thinking at the Oxford Martin School (INET Oxford). We mulled over his work as an advocate for a rewrite of dogmatic economic thinking, and discussed his views on the broken social contract and climate change. A true polymath, he has had an illustrious career in both the private and public sectors, maintains various teaching and research commitments at, amongst others the Santa Fe Institute, and is a regular contributor to various publications including the Financial Times, Bloomberg, The Atlantic, and many others.

CFM:

For those unfamiliar with the Institute for New Economic Thinking at the Oxford Martin School (INET Oxford), can you describe its main objective in a couple of words?

EB:

Our core motivation is to understand the real world.

Before I came to Oxford, I was at McKinsey for 18 years where I noticed a huge disconnect between the theories from my economic training and the reality of the business world. Since then I have become part of a broader movement to try and reform economics and bring it more in line with the messy complexity of the real world and to bring in ideas from other disciplines.

To that end, I established the INET Oxford centre in 2012 in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis to pursue that agenda, by setting up an interdisciplinary team of physicists, mathematicians, economists, sociologists, and environmental experts to try and understand the economy as it really is and how it functions. This research agenda is organised under a set of research themes – financial system stability, economic inequality, economic growth and innovation, the economics of environmental sustainability, and the moral and ethical foundations of the economy.

CFM:

The term ‘New Economics’ can be viewed as quite ambiguous. Is its main advantage as a challenger to the long-held supremacy and insularity of neo-classical economics simply, as you said, its interdisciplinary approach, or is it something more subtle?

EB:

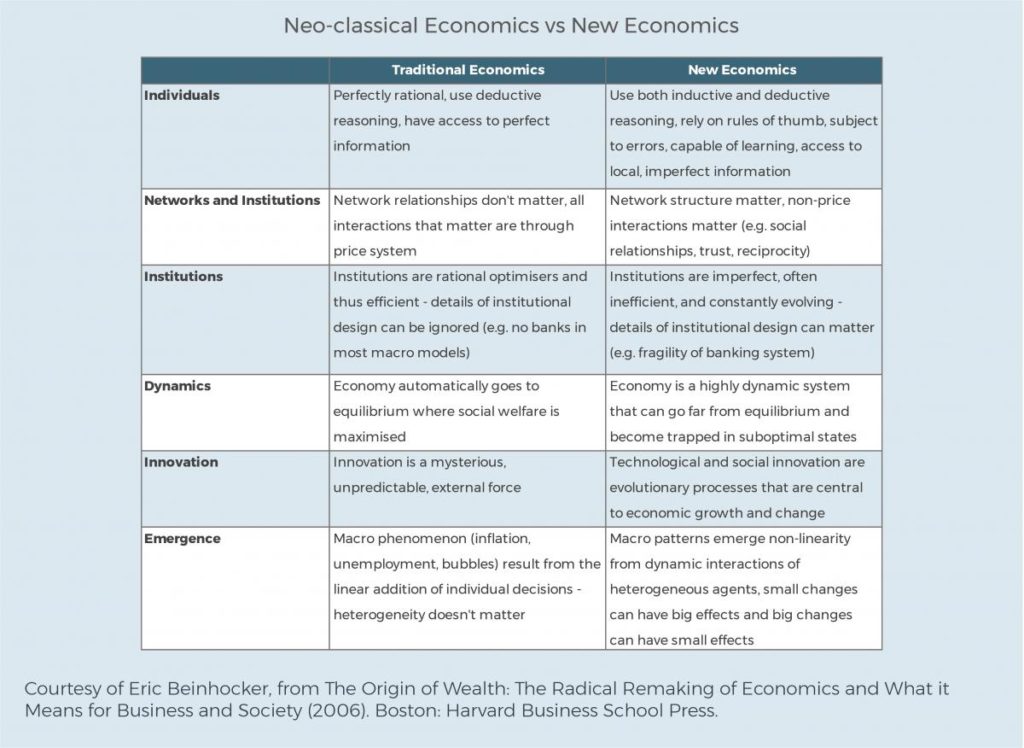

I agree that the label “new economics” is quite ambiguous, but I do think there is a big shift underway in how we think about the economy. As you said, the neo-classical model has dominated economics since the late 1800s. Even from its earliest days people criticised neo-classical models for oversimplifying things. In fact, the French mathematician Henri Poincaré wrote to his fellow countryman, Léon Walrus – the father of the neo-classical model – saying his model was mathematically beautiful, but he couldn’t see what it had to do with the real world.

Similar critiques have followed it around ever since. In more modern times we’ve had critiques from psychologists about unrealistic behavioural assumptions, critiques from sociologists and political scientists about not including factors like institutions and power in models, and critiques from statisticians about the often-poor performance of models versus real world data.

The harder problem has been: what are the alternatives? It is only in the last couple of decades that a true, feasible alternative has begun to form, coming from a variety of angles, notably from the theory of complex systems, but also from theories of cultural evolution coming out of anthropology; theories of multi-level selection coming out of evolutionary theory, along with insights from the cross disciplinary revolution in behavioural sciences (e.g. psychology, cognitive science, neuroscience) amongst many others.

We have seen reform efforts within mainstream economics to introduce behavioural economics, and introduce more institutional realism, but there has also been a desire to hold onto core aspects of the neoclassical framework, notably regarding the economy as an equilibrium system – a system that self regulates and naturally reaches an optimal resting state.

This last point is what I consider to be the biggest difference between traditional economics and so-called new economics. In this newer theory we are not constrained by equilibrium, instead we see the economy as a dynamic, constantly evolving system that is sometimes stable, and sometimes far from stable. New economics is not constrained by the equilibrium ideas from the 19th century, but instead starts with a clean sheet and asks, given what we know today about different kinds of systems in the world, what kind of a system is the economy?

CFM:

Some contemporary economic thinkers are questioning, for example, many of the measures of the neo-classical model, especially GDP – arguing that chasing ever higher rates of GDP is counterproductive and environmentally unsustainable? Is this something that you and your peers within the New Economics movement are sympathetic to?

EB:

Yes, the debates between theory and metrics are indeed very closely connected. The framework of GDP as a way of measuring economic output or activity was developed between the Depression and World War II, but the theoretical justification for GDP at the time was that it could serve as a loose proxy for people maximising their individual happiness or utility by consuming goods and services in the economy. However, this use of GDP as a proxy for human welfare has been criticised by many economists, including Simon Kuznets, one its developers in the 1930s, and more recently Joseph Stiglitz. Nonetheless, “more GDP is good” has become the mantra of policymakers and the media.

But when you start questioning the foundations of the theory, you question what actually makes good lives for individuals, because people obviously desire more in life than just more stuff, in particular research shows that our social connections, health, and physical environment are critical components of well-being. Furthermore, GDP does not take into account the damage all of our consumption is doing to the environment, nor the economic and social inequalities in the system, thus it raises questions about whether we are measuring the right things, and, as such, question about whether our policies are aimed at the right metrics.

New Economics will inevitably produce a new set of ideas as to what contributes to human well-being, what the goals of the economy are, and how we should measure progress towards those goals. In fact, literally as we speak, I am writing a commentary piece on a just-published paper by a colleague Dennis Snower (see Recoupling Economic and Social Prosperity[1]) with several interesting proposals on that.

“GDP does not take into account the damage all of our consumption is doing to the environment, nor the economic and social inequalities in the system…”

CFM:

Jumping to more contemporary matters…

Your home country is experiencing what seems, to many outsiders, as a potential water-shed moment in its political discourse. In many respects, one is reminded of the thesis of “Pitchfork economics” posited by your co-author Nick Hanauer, i.e. that radical inequality and societal injustice is most likely to lead to social uprising. Do you think a tipping point has been reached in the US?

EB:

I think we have already tipped, but the question is into what?

To back up a bit: you can’t understand what is happening in the US, and many other societies more broadly, just through the lens of a traditional rational actor maximising his or her utility, within the framework of efficient market economics. It must be seen as a failure of the policies that came out of that particular view of the world, what some call the neoliberal policy consensus that developed in the 1980s.

What we have seen over the past four decades is a huge shift in economic rents, going from people who work for a living to those who make their money from capital—something on the order of $2.5 trillion in the U.S. alone. As a result, of this massive re-allocation of the economic pie, incomes for 90% of the US population stagnated over decades, social mobility dropped, and inequality rose.

Modern behavioural research tells us that it is not so much inequality per se that is motivating people to take populist positions (and surveys show that most people are unaware as to just how unequal the US currently is), but rather a deep sense of unfairness. People believe the system is rigged, that it is not working for them, and that even if they work hard and play by the rules, they don’t see their or their children’s lives improve. Life has also become riskier to boot, specifically vis-à-vis unaffordable healthcare and retirement saving shortfalls.

In short, there is broad feeling that the social contract is broken—both on the political right and left—which is leading to populist politics and conflict.

I think the only way out of this mess is to fundamentally repair the social contract and create a fair deal for the majority of people.

CFM:

I want to pick up on your comments on repairing the social contract. Something one has to bear in mind is the role the political process invariably will play. But, with political division in the US at historically high levels, how likely is this given this level of partisanship?

EB:

The challenge is that repairing the social contract will require major changes in everything from market regulations, to worker pay practices, healthcare, social programs, education, retirement security, corporate governance, taxes, etc. Such deep structural change requires political unity to overcome powerful vested interests—something it is hard to see happening anytime soon.

The Harvard sociologist Robert Putnam has a new book coming out with some evidence that political division in the US is at a level not seen since the Civil War. The causes are a complex brew of demographics, shifts in the economy, social changes, ideological changes, and shifts in technology and the media, and have been brewing for decades.

Nonetheless, there are reasons to hang onto a kernel of optimism. When you dig into the data on the attitudes and values of most American voters, there is a huge amount of common ground. Any differences, however, get fanned strongly by politicians and social media. The key is therefore fixing the institutions of democracy (e.g. voting reform, campaign finance reform) so that the underlying consensus can manifest itself and the conditions become ripe so that the social contract can be fixed.

Some of this may come from the political dynamics that need to play out and exhaust themselves until people see no alternative but to build a new consensus – one side is not going to permanently dominate over the other, and the US, like any democracy, needs a spectrum of political views. The hardest part is rebuilding trust in the political institutions to enable that new consensus to form, at a time when some seem to be doing their darnedest to tear down that trust.

A second factor which is a cause for optimism is the generational shift: when you look at the data by age group, you see a break between Millennials/Gen Z-ers vs. Baby Boomers/Gen X-ers. The generation coming up sees the critical need for systemic change and appears more unified in its views on the values around that.

CFM:

One may naturally extend this notion of trust in public institutions to central banking, and to the Fed. You have publically raised concerns about some of the administration’s nominees for the Fed board. Is there anything that worries you about the direction of the Fed?

EB:

The independence of central banks has largely been a success story. Before the formation of an independent Fed authority, the US had major panics and financial crashes on a very regular basis. History in the UK, before the Bank of England was de-politicised, showed a similar pattern, namely that policy and policy responses are more stable and predictable under independent central banks with clear policy objectives.

Of course, central banks have to be constrained in a democratic political framework, but they should be given the latitude to take a longer term view and bring to bear all the expertise available to them.

We have seen the current administration, twice now, propose Governors for the Fed who have views in direct contradiction to independence, with very politicised views. There have also been, as you may well know, proposals in Congress to heavily limit the Fed’s independence.

All of these developments, in my view, are very dangerous. The US’s privileged position as issuer of the world’s reserve currency is underpinned by the credibility, stability, prudence, and expertise of the Fed. If that is lost, the damage to the US, not to mention the entire world economy, would be incalculable.

CFM:

Moving onto a more internationally tilted discussion…

Some of your colleagues have argued in favour of some form of coordinated macroeconomic policy response to the COVID-19 induced crisis. Assuming that you are supportive of their assessment, and given that we find ourselves in a sort of ‘G-zero’ world à la Ian Bremmer, is proposing international cooperation wishful thinking?

EB:

At the moment it is easy to be pessimistic about any sort of coordination. If you look at the reality of what has happened since the crisis though – and this goes back to our earlier discussion about independent central banks, the major independent central banks have actually been coordinating pretty well.

Yes, coordination has been much more limited at the G-20 level – we are certainly not seeing the same level of coordination we saw coming out of the 2008 financial crisis.

However, given that so many countries have embarked on historic fiscal stimulus measures domestically, I’m not convinced a roundtable-like G-20 huddle, akin to what happened during the last financial crisis, would have been that much more beneficial. Although, going backward on the trade agenda certainly isn’t helping…

Where I think the lack of coordination will start to bite is when governments exit from recently deployed stimulus. In an uncoordinated withdrawal of stimulus measures – especially when some countries either exit or limit these measures prematurely for, typically political reasons – that could slow a global recovery. Especially when this is going to be combined with potential second or third waves of the virus.

CFM:

Would you consider the recently proposed stimulus measures in the US, i.e. the extending, but lowering of unemployment insurance as a premature withdrawal?

EB:

Economically it makes no sense. There is somewhere in the order of 30 million people relying on these benefits, with only around 5 million new job openings. It is clear that there will be a tail of higher unemployment for some time and supporting a transition back towards a functioning economy makes both economic sense, as well as supporting the moral case of not leaving millions of families struggling to provide for their most basic needs.

Given the huge deflationary pressures that a collapse in demand has generated, maintaining strong fiscal support is a macroeconomic necessity, along with the monetary policy measures that are, in any event, likely to remain accommodative for some time to come.

Bear in mind that it is not just the US that risks exiting too soon – the winding down of the furlough scheme in the UK looks equally premature: there is a recent study by The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) in the UK showing that the measures, if continued into early next year, would more than pay for themselves in macroeconomic benefits.[2]

CFM:

You hinted at a very heated contemporary debate, namely the likely path of prices. Do you think that policy might overreach, stoking inflation?

EB:

Is there a risk of inflation? Yes. One can draw up many scenarios where inflation is likely to accelerate, but they are mostly low probability scenarios. The main scenarios that might cause higher inflation, or inflation in excess of targets, is if there is a strong bounce back in consumer demand, while supply chains are still constrained – and any such imbalances would likely be very short-term. The evidence, thus far, is that the contraction has been demand-led: supply chains have for the most part remained intact, while demand has lagged behind.

The role that monetary stimulus plays is often misunderstood – I think many folks are not fully aware as to how central bank balance sheets work. After 2008 there was a fear that the expansion of central bank balance sheets would lead to hyperinflation, but, of course, this did not materialise. We also saw this in Japan, in their ‘lost decade’, when despite a massive expansion of the Bank of Japan balance sheet, inflation remained muted.

Another reason the big expansion of central bank balance sheets doesn’t bother me that much, is because they are all doing it together. The bond vigilantes typically come out when one country gets out over its skis and overextends itself. But this is a global crisis, this isn’t due to the incompetence of any one government.

Money has to go somewhere… Even if the Bank of England has hugely expanded its balance sheet, Gilts will still remain attractive for a large number of investors.

Likewise, the fiscal stimulus seems entirely in line with the scale of the crisis, and again the risk is more on the demand side where, if stimulus measures are stopped too soon, deflationary forces will dominate and we’re likely to have a period of stagnation. The Fed clearly recognises this risk and recently announced it would tolerate a slightly higher inflation target in pursuit of reducing unemployment.

“One can draw up many scenarios where inflation is likely to accelerate, but they are mostly low probability scenarios.”

CFM:

While CPI as a measure of inflation did not accelerate post GFC, would you, however, agree that the expansion of central bank balance sheets after the GFC did, one can argue, lead to inflation of prices of financial assets?

EB:

First, I often wonder whether aggregate consumer inflation is even a useful measure at all – I’m not entirely sure it tells us anything useful about the economy. My group at Oxford has done extensive work looking at the long-term price trends of a huge variety of goods, and, when you look at inflation at the level of individual goods and services, you see a widely dispersed fan chart – some prices declining at very steep rates such as electronics and telephony, while the prices of goods and services such as healthcare, education, and housing (in some regions), keep going up very steeply. When you look at the aggregate given such diversity, it is not clear that it is such a useful measure. Moreover, the drivers of those price trajectories are also very dissimilar – Moore’s law is driving the price decline of goods such as electronics, while institutional arrangements such as the patchwork of the US healthcare system is driving healthcare costs.

When Milton Friedman said that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, he was wrong. There are various secular as well as macro-monetary conditions that are driving prices, and in actual fact, in recent history, macro-monetary conditions have been a minor player in price levels largely because of the success of central banks in containing broad inflation.

Asset price inflation, however, is a separate matter. It is clear that the Fed actions have played a major role in asset price movements – we saw it in 2008, and we are seeing it again now. The financial markets have experienced a V-shaped recovery since the onset of the COVID crisis largely due to the “Fed put”, while the future path of the real economy remains highly uncertain. This of course further exacerbates the inequality between wage earners and asset owners we discussed earlier. It is a big problem that our most powerful macroeconomic policy tools in essence only seem to work by inflating asset prices for already very wealthy people. It makes one question what good financial markets really are doing for society.

“When Milton Friedman said that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, he was wrong.”

CFM:

When you say how they work, do you subscribe to the idea that the market is no longer an effective allocator of capital?

EB:

Public equity markets are not a big source of capital – almost all the activity on public equity markets is trading of existing assets. There is very little new issuance, and IPOs are becoming ever rare. Most new capital comes from bond markets or private markets such as venture capital or private equity, or financing from internally generated cash-flow.

Other factors come into play above fundamental company performance that drive valuations of individual equities and other assets such as the herd-following nature of asset allocation schemes, constant rebalancing, the huge rise of indexing, along with macroeconomic forces in the form of, amongst others, a wall of money coming from the Fed.

It is not so much the notion that markets have detached from reality, but rather that the nature of reality has changed. The markets are not so much reacting to what we would think of fundamental microeconomic notions but reacting more and more to tidal macro forces.

CFM:

I would like to finish by jumping straight into a topic that have occupied much of your research and interest lately, Climate change.

And I’ll begin with a more fundamental question, which is often at the heart of climate change discussions: Why do you think so many ‘reasonable’ people doubt science, and why do you think this is so pervasive in our current discourse?

EB:

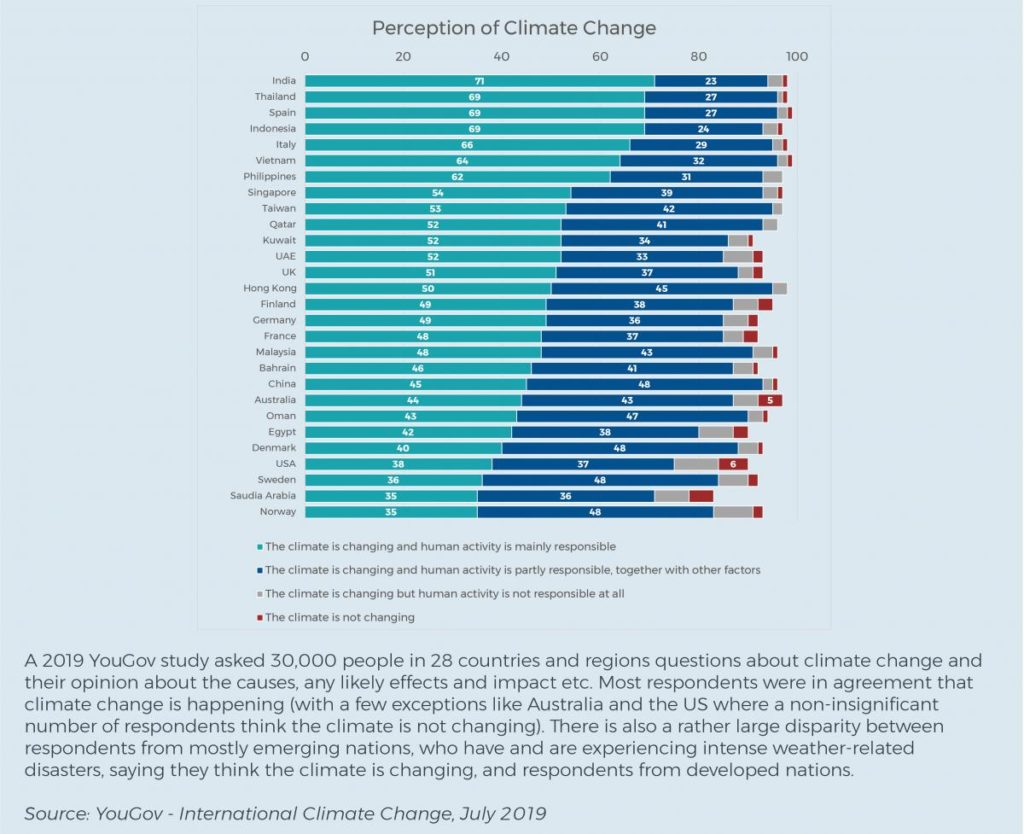

I think it comes back to an earlier point, which is the loss of trust in institutions and authority. And, maybe, with some good reason, it is because the ‘elites’ have not done a tremendous job on many issues of late.

But there are equally, fundamental reasons behind this.

Decision science shows that people don’t make decisions based on rational calculations or science, they make decisions more heuristically, based on who they trust; whose opinion they value or believe; what connects with their values and simply, often what feels right or reinforces their preconceived view of the world.

Earlier consensuses around science were based on people being generally more trusting of authority, including, mostly, having a set of values that science is good, with friends and neighbours sharing similar entrenched values.

Much of this trust has regrettably broken down, exacerbated by those with an agenda and self-interest, seeking to undermine that trust. We saw, for example active campaigns in tobacco to shoot down the science between smoking and cancer. And we saw, a very deliberate campaign, by the fossil fuel industry and others with similar interests, to raise questions about climate science. Decades ago, climate change and the environment were bipartisan issues and conservatives including Richard Nixon, George HW Bush, and Sen. John McCain took strong pro-environmental stances during their careers. Sadly, in the US, Australia and a few other countries, climate science denial has become a signal of tribal loyalty on the political right and bipartisanship has all but disappeared. When I first started working on this issue the 2020s were way off in the future and seen as a benchmark decade, the point where emissions need to peak and start declining to avoid true catastrophe. We’re now there, we wasted decades, emissions are still rising rapidly, and we’re starting to see planet-wide consequences from mass species loss, to ice sheet and glacier loss, super storms, fires, etc.

The good news is, again, when you look at the attitude of younger generations, most see climate change as the greatest risk they face and accept the science. But unfortunately, we can’t wait for this next generation to get into power to change things – if we don’t act it will be too late and they will never forgive us.

[IMAGE]

CFM:

When you mention a shift in attitude, there is a related shift that is leading to the decay of the Friedman doctrine in favour of more stakeholder value creation. Do you think there are clear winners that are most likely to take advantage of this shift and thrive?

EB:

First of all, history will show that the primacy of shareholder value was actually more of an aberration than a central tenet in the chronicles of business. If you read business history, you realise that companies were managed on a multi-stakeholder-like model for most of the 19th and 20th centuries, and then, only from around the 1980s to the 2000s, we had this near-religious devotion to Friedmanite shareholder value. The Friedmanite doctrine is badly flawed on many levels and has done a huge amount of damage, not just to workers, communities, and the environment, but also to the long-term health of the companies themselves (my Oxford colleague Colin Mayer wrote an excellent book, Prosperity, on this).

I see the raising of expectations of what CEOs and boards are supposed to do as being not at all inconsistent with good economic outcomes. It is not unreasonable to expect CEOs to be able to walk and chew gum at the same time, to be able to deliver a necessary return to their shareholders to justify holding their capital, but at the same time to avoid, at a minimum, doing lots of damage to society – whether the environment, treatment of their workers, or treatment of their communities.

The winners will be the firms whose leaders actually understand that their world has changed and are up to the challenge of building their companies to meet that new reality. If they are in denial and think that they can keep doing business in the ‘old way’, they will be the losers. We have to assess management teams through a new lens.

CFM:

What do you deem to be the number one environmental risk facing the planet?

EB:

The collapse in ecosystems and mass extinction that it is causing should be a worry for one and all – and the data we are seeing is getting worse all the time. Any notion that humans can live and thrive when the rest of life on the planet withers would be absurd. This is not just climate change but reflects the totality of the impacts we have on the planet, from the effects of toxins and pollution, to land use.

Economists have historically treated the environment as a cost-benefit trade-off problem – that is what William Nordhaus recently won his Nobel Prize for. But that frame is deeply flawed in two ways. First, is the assumption that a sustainable economy is somehow more “costly” or less economically efficient than an unsustainable economy? One might be forgiven for thinking that in the 1990s, but we’ve now had decades of evidence showing this is simply not true. There is a large one-time investment in new infrastructure required, but this in itself is hugely stimulative for the economy and then once made the long-term benefits are immense. And second, the “benefit” of avoiding planet-wide ecological collapse and mass extinction is essentially infinite. People forget this is a one-way ticket, if we lose the ecosystems that support human and non-human life, they’re not coming back on any human time scale.

CFM:

What would you regard as the number one solution, whether it be policy derived or not, likely to mitigate this risk?

EB:

There are no magic bullets, but my Oxford colleague Kate Raworth has a very good framework for asking the right question. Her famous “Doughnut Economics” chart looks at the physical constraints of the planet, and what scientist call a ‘safe operating space’, and then marries that with achieving social goals such as quality of life for people. It requires a huge transformation – in our physical infrastructure and our social institutions. But it is well within our capabilities, there are numerous “pathways to zero carbon” studies that show we have the technologies and knowledge. And humankind has gone through other such big economic-social transformations before, e.g. the Agricultural, Industrial, and Computing revolutions. The difference with this transformation however is we can’t just wait until it happens organically, we have to deliberately and dramatically accelerate it. That is something humanity has never done before.

So, the big existential question is whether future generations (assuming they exist) will look back on our era and say “they did it!” or will they say, “they could have, but didn’t”?

Eric spoke with André Breedt, Research Associate in our Paris office.

[1] Interested readers can find the paper here: https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/12998/recoupling-economic-and-social-prosperity

[2] See https://www.niesr.ac.uk/publications/covid-19-impacts-destitution-uk

Readers can follow Prof Beinhocker on Twitter.

And can learn about his research here.

For details of his book, The Origins of Wealth: Amazon

For more information on the Institute for New Economic Thinking at Oxford: INET Oxford

DISCLAIMER

THE TEXT IS AN EDITED TRANSCRIPT OF A PHONE INTERVIEW WITH ERIC BEINHOCKER IN JULY 2020. THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN THIS INTERVIEW ARE THOSE OF ERIC BEINHOCKER AND MAY NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE OFFICIAL POLICY OR POSITION OF EITHER CFM OR ANY OF ITS AFFILIATES. THE INFORMATION PROVIDED HEREIN IS GENERAL INFORMATION ONLY AND DOES NOT CONSTITUTE INVESTMENT OR OTHER ADVICE. ANY STATEMENTS REGARDING MARKET EVENTS, FUTURE EVENTS OR OTHER SIMILAR STATEMENTS CONSTITUTE ONLY SUBJECTIVE VIEWS, ARE BASED UPON EXPECTATIONS OR BELIEFS, INVOLVE INHERENT RISKS AND UNCERTAINTIES AND SHOULD THEREFORE NOT BE RELIED ON. FUTURE EVIDENCE AND ACTUAL RESULTS COULD DIFFER MATERIALLY FROM THOSE SET FORTH, CONTEMPLATED BY OR UNDERLYING THESE STATEMENTS. IN LIGHT OF THESE RISKS AND UNCERTAINTIES, THERE CAN BE NO ASSURANCE THAT THESE STATEMENTS ARE OR WILL PROVE TO BE ACCURATE OR COMPLETE IN ANY WAY.