Lord O’Neill has had an illustrious career spanning more than three decades, much of which was spent at Goldman Sachs where he was named Chief Economist. He ultimately became Chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management before retiring from the firm in 2013. Amongst his many accolades, he perhaps became most known and associated with the term ‘BRICs’, coined in a landmark 2001 paper entitled ‘Building Better Global Economic BRICs’. He subsequently served as Commercial Secretary to the Treasury, and was appointed in 2014 by then Prime Minister Cameron to head an international review on global antimicrobial resistance. He is currently the Chairman of Chatham house, sits on the board of various think tanks and international organisations, and remains an active contributor for various media outlets. We had the pleasure of meeting Lord O’Neill at The Arts Club in London for a chat on noise, narratives, and natural language processing.

CFM:

Noise…! We deal with evermore, and endless streams of ‘information’. What is your approach as an economist on cutting through the noise?

JN:

During my whole professional career, I used to think it was my most important task: to figure out what was noise, and what was news. Most of what we absorb every day is mostly noise, and the advent of social media, at least superficially, makes distinguishing between noise, and what is significant much harder. It is one of the reasons why I personally chose to avoid social media. I never had Facebook, nor twitter, for I can’t see, other than for increasing the amount of noise in my life, how it can be constructively beneficial.

However, although it might seem particularly crazy these days, I’m not sure it’s much different to what it’s ever been. Sure, if you get sucked into modern communication channels then it can feel that the noise-to-news ratio has changed, but I don’t believe it has.

CFM:

Would you subscribe to the notion that the bevy of new tools such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and Natural Language Processing (NLP) etc. have the potential to cut down that ratio?

JN:

I think the obsession about AI etcetera is part of the noise. From a forty-thousand feet view, you see ourselves living through an era of incredible tech-related developments, supposed to be improving our lives, a boon for productivity, yet, at least with the data we have, measured productivity throughout the Western world has collapsed. Do these things truly increase productivity, or do they too often act as an unnecessary distraction – I am not yet that convinced of the former.

CFM:

The European Central Bank (ECB) recently released a cache of speech transcripts, hoping, amongst others that it “will stimulate natural language processing research on the impact of our speeches on the market and beyond”. Do you have any confidence in NLP techniques, apart from the benefit of speed, capturing the importance or sentiment from such communications?

JN:

Mario Draghi delivered, arguably, his most important speech here in London, one day before the start of the Olympics. I was sitting twenty yards away from the podium when he said that the ECB will do “whatever it takes to preserve the euro”.

I was still at GSAM [Goldman Sachs Asset Management], and hundreds of the world’s most significant asset managers were sitting in the room. I immediately realised the gravity of his words, and discussed it with him afterwards. But, I would imagine, if you did testing on that particular speech, it would be many standard deviations away from the regular stuff that is likely to register as a ‘significant’ event. For those savvy enough, they however would have been quick to react. Anyone who bought Italian bonds at that time for instance, would have been a very happy chap.

Having an algorithm or a tool delving into the weeds of everything the ECB has ever published, or ECB Executive member ever said, academically might be curious, and, if part of a business is uniquely to deal with ECB reaction functions, it might reveal some marginal interesting results. But in the scheme of things, there are, I would call it no more than ten moments in the entire history of the ECB where what was said was truly important.

CFM:

Turning to some contemporary economic topics. A theory of ‘secular stability’ has been proposed to explain lower volatility – not only in financial markets, but also in global economic data. How do you think this low volatility marries with a seemingly endless list of uncertainties and risks in the world today?

JN:

Two things. First, linked to our discussion thus far – I am not sure it is as uncertain as everyone claims. From my experience, things are always uncertain. What is different, nowadays, is that many more have confidence about there being uncertainty. I think that the perception of uncertainty is often overblown by professionals. Markets are, and have always been uncertain. I don’t think they are necessarily more uncertain than in the past.

And secondly – much of this uncertainty is ascribed and linked to the rise of less-conventional political forces in Western countries. That is not so obviously peculiar to me, given what has transpired over the past twenty years. Arguably, capitalism has not worked as it was supposed to in textbooks, and it moreover coincided with a period when the mainstream political classes moved to the centre. Those who were left unable to benefit from the remarkable twenty years of globalisation, needed a new voice to protest. So whether it be the Five Star movement in Italy or Nigel Farage here [in the UK], or Trump – there is a certain logic to what has transpired, which in my opinion, other than the fact that it is frustrating for many of us who have come from this highly centralised ‘elite’… for want of a better word, does not translate into uncertainty. From a narrowly educated and trained point of view it might seem uncertain, as opposed to something that hasn’t been properly anticipated. But there is a difference.

CFM:

I think you’ll then agree with Robert Shiller’s new book “Narrative Economics”, in which he draws the parallel between people’s obsession and fear about losing their jobs due to AI today, and that of ‘Labour saving machines’ in the late 19th century, and ‘Automation’ in the 1950s? It is the same thing he claims, but merely a different set of events, circumstances and taxonomy in the past, and in fact, the level of ‘uncertainty’ was much higher in the past than today.

JN:

I completely agree with that. We have seen this play out in all of human history. People get sucked into fads and fashions. There is, however, notwithstanding the danger of oversimplification, little evidence to support that this time will be any different to the past.

CFM:

A clear candidate for becoming the defining ‘narrative’ and one of the definitive driving forces in the economy over the coming decades is climate change. Do you agree?

JN:

Let me start by making, again, a possibly controversial statement. It is certainly one of, if not the biggest societal market failures, but, I am not wholly convinced it is the most important.

I am particularly sensitive to this debate, having spent a large part of the past five years working on, and advocating for research in antibiotic, or antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which, in terms of killing people over the coming decades, is highly likely to be much more devastating than climate change. It intrigues me that there isn’t as much attention on AMR as there is on climate change. I occasionally ask: “Where is AMR’s Greta Thunberg?!”

And, I facetiously wonder whether the scale of the obsession of climate change has an element of noise in it? I equally wonder why society isn’t as focussed on solving AMR problems, as it is on solving climate change.[1]

In any event, I think we are in the very early stages of an era where there will be a resolve of business to play a much more inclusive role to address society’s most pressing issues, whether it be climate change, or whether it be AMR. I suspect business will have to discover more purpose beyond delivering pure returns to shareholders, to play a more active role in solving these issues.

CFM:

Where to for oil & gas companies? How do you respond to those that advocate for the divestment from these firms?

JN:

We at Chatham House have discussed this very topic as it relates to our own endowment, and considered whether we should guide our investment managers to limit their exposure to fossil fuel companies.

My take, and the analogy I used, is that one of these companies may very well be the modern version of Nokia – who used to be one of Finland’s major, if not the major pulp and paper producer. It reinvented itself to become, albeit for a brief period of time, the leading mobile phone producer in the world. To divest from all these companies, in an apparent bid to force them out of business, I don’t think is particularly wise.

Some of these large oil and gas companies have every chance of reinventing themselves. Helping them with incentives to be at the centre of finding solutions for the problem is in my view the best policy.

CFM:

This is a popular counter argument. Why do you think some investors remain adamant about excluding these firms?

JN:

It partly goes back to what we discussed earlier – investors have to contend with popular, human fads. I chair a board who are rightly wary of being blamed for anything related to fossil fuels and climate change. Many investors are grappling with the same dilemma – they might say “I don’t care if I am being illogical, I just don’t want to be on the TV with Greta Thunberg pointing her finger at me”.

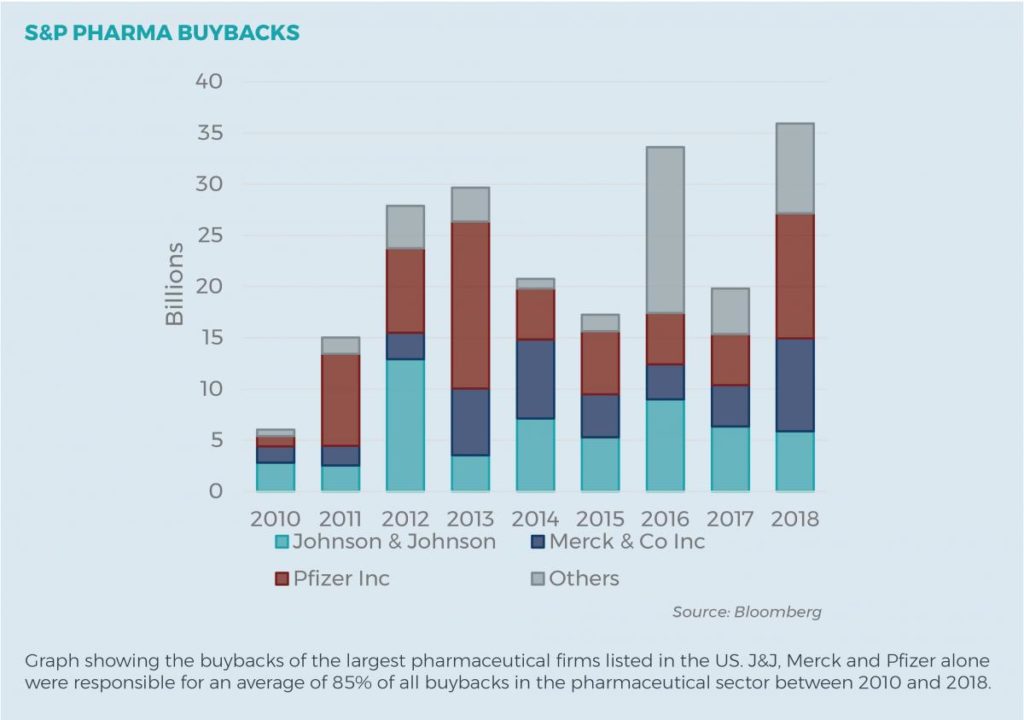

There are, incidentally, plenty of tangential things with AMR, which our review[2] projects will cause 10 million deaths by 2050. To meaningfully address this threat, we estimate, would require funding of $42 billion. But pharmaceutical firms are slowly getting out of the business, largely owing to a lack of returns in the short-term. And, to put that figure into perspective, I offer this statistic: in the first five years of the 2010s, J&J, Merck and Pfizer alone bought more than $42 billion of their own stock. And yet, society is faced with a dilemma that is likely to cause millions of deaths.

The way to solve this impasse, is not to force companies out of business, but to prompt a change in the risk-returns calculation of the CEO and management of those companies, with the same logic for climate change. Adjusting capital adequacy ratios for targeted investment purposes such as clean energy businesses, or AMR, is I think one policy worth exploring.

CFM:

In summary then, and as you alluded earlier, common thinking about shareholder vs. stakeholder maximisation are parting ways with the Friedman doctrine…What do you think might be the optimal balance between regulation, and self-regulated business incentives?

JN:

Rules and regulations force behaviour down a certain path. If you want to change the path, change the rules by changing the incentives and the risk-reward dynamics. Of course, the difficult bit is that regulators are typically reactive, responding to the past, rather than anticipating the future.

CFM:

Any outrageous predictions you care to make for 2020?

JN:

I do wonder – not with any great amount of confidence – but I do wonder whether we are getting more ingredients that will usher in the end of the fixed income bull market. It seems to me there are essentially three ingredients that drove the past forty year bull market in bonds: suppression of inflation; the past decade of quantitative easing (QE); and fiscal respectability. All three of these forces are changing.

Firstly, owing to the social challenges of income and wealth inequality in particular, a number of large Western nations are deliberately changing minimum income laws – in the UK for example, during the election [the 12 December 2019 UK general election], both major parties voiced their intention to raise minimum wages significantly.

Secondly, there is likely to be substantial fiscal expansion in the UK, and likewise in Germany and Japan.

And lastly, some of the leading, independent central banks are coming to the view that unconventional monetary policy has become counterproductive. The Swedish Riksbank, who, in my view, is one of the sharpest thinkers on inflation targeting and QE, have been raising rates. And I foresee a shift, a change in the mindset in the same direction.

Going into 2020, these three things are likely to collide, making it not inconceivable that we are moving into a more volatile period for bonds.

CFM:

Picking up on your comments about monetary policy, do you think it is a natural conclusion that central banks might move away from inflation targeting, or at the very least, effect a major rethink about the target levels as was hinted by Mario Draghi?

JN:

I think central banks should move away from thinking of economics as a science. I think getting rid of the 1960s/70s problem of vicious inflation cycles has been a good thing, but it has been replaced by an excessive, and lingering confidence in the Phillips curve. Macroeconomic analysis has for decades relied on the trade-off between unemployment and inflation – a tenet of economic orthodoxy that has not born out since at least 2008.

CFM:

In Mario Draghi’s farewell remarks, he called for a more “active fiscal policy in the euro area”. Do you think new President Mme Lagarde has the ability to curry enough favour in European capitals to promote fiscal expansion?

JN:

I think she is fortunate that it is becoming so obvious, especially in Germany, that it might be easier to persuade them. For the monetary union to ultimately survive, Germany needs to loosen its rigid stance on fiscal policy. If the ECB’s inflation target is, or remains just below 2%, that requires a country like Germany to occasionally, and willingly have inflation running quite a bit more than 2%. Otherwise one is subject to the likes of Italy in permanent monetary deflation – a situation which is untenable.

CFM:

Switching briefly to the dominant theme of 2019. Having spent a large chunk of your career analysing the Chinese economy – do you think they have the economic firepower to withstand an extended, and uncertain trade war with the US?

JN:

This can keep us busy for hours, but let me summarise:

I don’t know.

I do worry about certain aspects of China, more than I’ve ever done.

Because China has become one of the dominant economic powers, it is struggling to deal with its global importance. The one-party system isn’t trained to deal with those who are not part of the one-party system – you observe this in the scraps China have picked up expanding its Belt and Road Initiative, and equally with the Huawei debacle and the trade negotiations. At the core of many Chinese challenges for the first half of the next decade is being wiser about their own presence in the world.

This unawareness is also observed in the behaviour of Chinese business interests and tourists abroad, and the perception that is being formed in Western nations. The Chinese will need to improve this perception – China will need to deliver a bit more subtlety.

China already has four times as many citizens, that every year earn as much as the average British or French person. There is no other place, other than the US, that has created that large a middle class. And yet, they still have half a billion people – at least – in low to very low income groups. Trying to keep both those groups content, is, I think, the greatest challenge facing Chinese policy makers. Lifting up the bottom part of the Chinese citizenry is the key to the sustainability of the Chinese model – if they can’t, it is very likely that the central party state might start losing control.

1. For further reading, a recent opinion piece by Lord O’Neill on Project Syndicate is recommended. Read it here.

2. Review of Progress on Antimicrobila Resistance, Chatham House, October 2019.

►

For more information about Chatham House, please see their website: www.chathamhouse.org

►

Lord O’Neill regularly contributes to Project Syndicate. See their website for a full history of his opinion pieces: https://www.project-syndicate.org/columnist/jim-o-neill

Lord O’Neill spoke with André Breedt, Research Associate in the Paris office of CFM.

DISCLAIMER

The text is an edited transcript of an interview with Lord O’Neill in December 2019 in London. The views and opinions expressed in this interview are those of Lord O’Neill and may not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of either cfm or any of its affiliates. The information provided herein is general information only and does not constitute investment or other advice. Any statements regarding market events, future events or other similar statements constitute only subjective views, are based upon expectations or beliefs, involve inherent risks and uncertainties and should therefore not be relied on. Future evidence and actual results could differ materially from those set forth, contemplated by or underlying these statements. In light of these risks and uncertainties, there can be no assurance that these statements are or will prove to be accurate or complete in any way.